The Measure of Time In Saranda

There will be a time someday in the future, when no one will even consider mining in a forest as beautiful as Saranda. Perhaps when corporate beings are extinct.

Saranda not only feels a historic place, or a mythical one, it even feels like an ancient witness to the forces of nature that are contradictions. An iron ore mine and a pristine forest. A mining town and an Adivasi village and it’s own relation to time. A CRPF camp and the routine harassment of motorcyclists, on the excuse of checking their vehicle insurance, the CRPF takes photographs of everyone. They are not from Jharkhand, the policemen are often aggressive.

The immensity of trees, the innumerable flora and fauna, and the single-minded aim of mining companies and their search for profit.

The mining conglomerate and the unemployed masses.

The RSS and the SPO’s in every village. The way the village deals with them.

A galaxy visible at night, and a young Ho Adivasi boy, almost every night, has to fix the electric transformer in his village. He takes a small copper wiring, makes a noose around it, and uses a stick to connect 10,000 volts to each other, to connect his village to the world.

The Gua massacre when the police in 1980, and the modern immemory of mobile phones.

A poor Ho woman receives a ‘pathal-making’ machine from the government. But the electrician installing it, and the government official, both want them to pay the electrician, without a receipt, 800 rupees, or 1,100 rupees. Thus the never-ending curse of exploitation, and the phantasm that is the welfare system.

The red rivers and the pristine ones.

Three mine workers are returning from their shift at Chiria mines. They are all old men. They walk to the mines through the hill and forest, and when they reach the mine, the manager berates them for being late. The man responds that he’s not like you, I don’t have a big car, or a bike or a horse.

In this forest, trees die naturally, and also unnaturally. Every detective in the world, would know who murders a tree.

Maoists who claim to fight for the rights of Adivasi people, who leave pressure bombs of landmines in the region, where a woman might go collecting mahua in the forest, and will lose her life or her leg.

Of course, the most immense contradiction that will be written down here, would be that of industrial development and land acquisition, versus a people who want their destiny in their own hands, that of resistance, that of Adivasi culture, that of a Hodisum.

It was in the early 2010s, when Vedanta had acquired a company called Dempo from Goa, when the threats of land acquisition in Dibuli, Guchadi, and parts of Kamarbeda and Duatambi, had become a palpable threat. They wanted to open an iron ore factory.

‘We made one of the dalaals a garland of slippers and we paraded him around the village,’ Said Budhan Surin, one of the elderly residents of Dibuli, which is actually a Tola of Guchadi, whose villagers had handed over their land to the company.

‘All of us went to the dalaals, the women, the old men, the young people.’

Even in the village of Kumbiya, around 20 kilometers away, a young man, Madan Surin explained how the dalaal threatened him for opposing the company. The dalaal is a young man whose lands are used for the village haat, ‘he gets ten rupees for a small stall, fifty for a big one, and a hundred for the biggest.’

‘So he earns enough money.’

‘And now he wants more.’

The struggle lasted years, Vedanta would try to win over a populace but a society with consciousness, knows how to ask the right questions. The dalaals and the company were eventually defeated but even now, old Budhram’s first question to me, was, ‘would any company come back?’

Because it is not yet scrapped on paper. According to the Land Acquisition laws, if the company doesn’t start work within five years, the land has to be returned to the villagers. The government circumvents this, by handing over the land to another company, and that company now can start at its own time machine.

‘Do the people of Guchadi come to the people of Dibuli?’

‘They do now, they realized their mistakes.’ Continued Budhram.'

Sushil Barla, one of the vociferous voices for the Adivasi people in Manoharpur is a well-known man among all those who resist the company. A resistance movement often has a soul, a center, and Sushil would be one of them. Even Budhram says, it was due to him, that they could defeat the company.

‘We win, when we speak about section 49-50 of the CNT Act, that states that wherever there is a religious space in the village, it cannot be acquired.’

‘For Ho people, even the kitchen is seen as a holy place.’

‘The munda-mankis don’t read the laws, don’t listen. If the company gives them alcohol and meat, they will agree to say yes, if we go and talk to them, then they say no to the company.’

‘We are not against mining.’ he clarifies, ‘we are against factories on Adivasi land.’

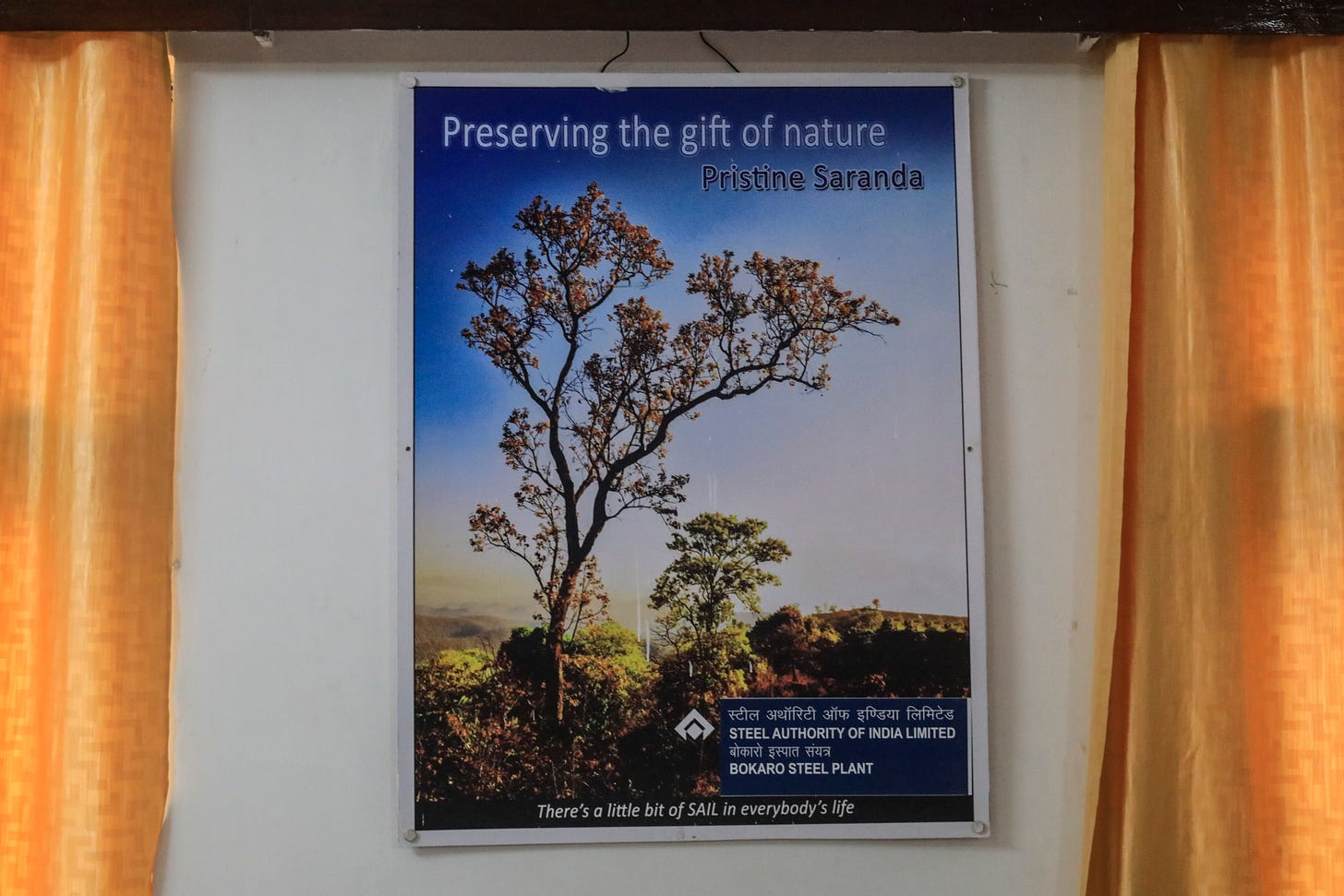

Further away in Kiriburu, is the impossible contradiction, of a poster in a SAIL company guest house: where the mining company says ‘preserving the gift of nature’, ‘pristine saranda.’

How does one photograph a forest? Does one take photographs from a distance of its density, or from a satellite, or a map, or does one have to capture every tree, in order to capture the essence of a place?

The answer, is obvious. The ancient trees, sacred groves and Adivasi histories are the measure of time in Saranda.